Let’s talk more about pound cake. Namely, its history and origins. I’d almost included this in my last post, but self control and restraint overtook me. Why throw away a perfectly good topic for a new post, afterall?

Like much of American food generally, pound cakes originate in Britain, possibly as early as the 16th century. Martha Washington’s manuscript cookbook was in the Washington family since at least 1749 (Hess 3), but the recipes date from “the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, or from the mid-sixteenth century to about 1625,” and thus are English (Hess 5). One recipe is for “excellent curran[t] cakes,” an early pound cake. “Take 2 pound of butter…2 pound of flowre & 2 pound of sugar…6 eggs to a pound of sugar & flowre…& 2 pound of currans” (Hess, 314-15).

This recipe neatly illustrates the likely origins of the cake’s name in its use of a pound of each ingredient. It has some cross-Channel ties with the French quatre-quarts or four-fourths cake. Larousse Gastronomique defines this as a “household cake mixture, made up of equal quantities of eggs, flour, butter and sugar,” or an “English Pound Cake” (Montagné 769). “Quatre-quarts” refers to the proportions of the cake’s ingredients, whereas the “pound” in pound cake refers to how those ingredients are measured. It’s possible that cupcakes are similarly named; not necessarily a cup of each ingredient, but a cup as the unit of measure (Olver).

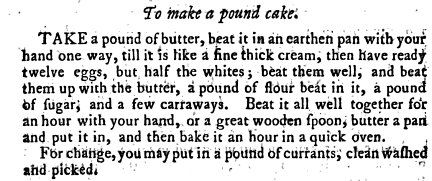

The earliest published recipe for pound cake doesn’t appear until Hannah Glasse’s 1747 The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy (Glasse 170).

Glasse’s must’ve had something right because it was lifted at least twice without credit in two other English cook books. First in John Farley’s 1783 The London Art of Cookery and Housekeeper’s Complete Assistant (Farley 292-93) and again in John Perkins’s 1796 Every Woman Her Own House-keeper (Perkins 140-41).

The first published American pound cake recipe turns up in the first American cookbook, Amelia Simmons’s 1796 American Cookery.

Pound Cake

One pound sugar, one pound butter, one pound flour, one pound or ten eggs, rose water one gill, spices to your taste; watch it well, it will bake in a slow oven in 15 minutes (Simmons 37).

Note the continued use of rose water, still common into the 19th century (Lohmann xii). And the “spices to your taste” were likely mace, as in the Washington recipe, and/or nutmeg or cinnamon, each popular at the time. Jas. Townsend & Son explains the odd baking time, suggesting it was portioned out as cookies (Jas. Townsend & Son).

Mary Randolph’s 1824 recipe in The Virginia House-wife, pretty much set the standard. She flavored hers with “lemon peel, a nutmeg, and a gill of brandy.” A bit old fashioned, yet recognizable and appealing. Randolph also advises eating it “with sugar and wine…also excellent…served up with melted butter, sugar and wine” (Randolph 161). Yes, please.

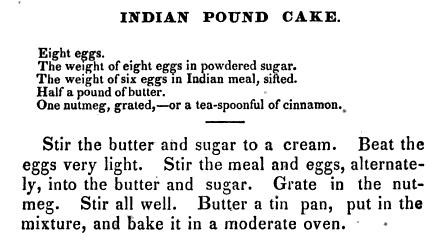

When pound cake crossed the pond, though, it sometimes changed in uniquely American ways. Eliza Leslie’s 1828 Directions for Cookery has a recipe for

“Indian meal” is cornmeal, that most American of ingredients. This mirrored the replacement of wheat flour with cornmeal in America generally as British expats tried baking British breads with American provender. Lost too is the rose water and dried fruit, foreshadowing the modern American ambivalence towards raisins (Spiegel).

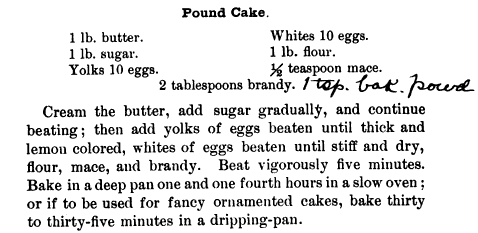

By and large, though, pound cake remained unchanged in its primary parts. It was still much the same in Fannie Farmer’s influential 1896 Boston Cooking-school Cook Book, and resisted the addition of newfangled chemical leaveners (Farmer 431).

Around this time, “cold-oven pound cakes” became popular with the advent of gas stoves (again, see my earlier post). By the 1930s, Americans still made pound cake, in a North Carolina example, with the same “pound each of sugar, butter,” eggs, and flour (Kurlansky 110). Recipes from Old Virginia has recipes for “Old Virginia,” “Old-fashioned,” “White,” “Crusty,” “Economy,” “Cream,” and “Simple” pound cakes, some still calling for mace, brandy, or wine and others now call for vanilla, leavening, or fats besides butter (Virginia 207-209). There are countless more in modern standards like Joy of Cooking (Rombauer 939-41), and the Better Homes and Gardens New Cook Book (Better 286). A quick Googling turns up nearly 10.5 millions results, Paula Deen’s topping the list (Deen).

Back in Britain, pound cake stayed close to its roots. Florence White’s 1932 Good Things in England has two pound cake recipes, one of which still contains currants and nutmeg, but was updated with baking powder. Modern British Madeira cake is the nearest Anglo analog to American pound cake, made with equal quantities of the same ingredients, but usually flavored with candied orange or citron peel (White 287).

I thought it’d be fun to give that earliest pound cake a go. Whereas Karen Hess can normally be counted on to clarify vague historic instructions, for this one she says “the mixing directions are awkwardly expressed, but clear enough, I think” (Hess 315). Think again. What I suspect the author is driving at is sifting all the dry ingredients together and then sieving that into the butter, then alternately with the eggs. It’s an unconventional method, but seems to work.

I did take Hess’s advice of adding whole-wheat flour to the all-purpose to approximate 17th century flour (Hess 118). Baking the cake on a preheated pizza stone replicates the properties of a stone-floored oven–a nice touch, but unnecessary if you don’t have a stone. Preheating the oven to 350°F and dropping it to 325°F at bake time recreates a “falling oven,” that is wood-fired to peak temperature and then decreasing temperature over time (Hess 19-20). The rose water is quite alien to 21st century palates, but not at all unpleasant and quite satisfying with a cup of milky tea. Well worth the effort for a sense of how a modern standard used to taste.

17th Century Pound Cake

Makes two 6-inch round cakes or one 8×4-inch or 9×5-inch loaf

226 g (1 cup) unsalted butter, softened

200 g (1½ cups) all-purpose flour

26 g (1½ tsp) whole-wheat flour

226 g (1 cup) granulated sugar

¼ tsp salt

¼ tsp ground mace

2 large eggs

1 large egg yolk

1 Tbsp rose water

113 g (2/3 cup) dried currants

Set a pizza stone (if you have one) on the center oven rack and preheat oven to 350°F. Grease and line tin(s) with parchment.

Beat butter until pale and fluffy. Whisk together flour, sugar, salt, and mace. Sift 113 g of the flour-sugar mixture into the butter and beat together.

Crack eggs into a small bowl along with the egg yolk and rose water. Tip eggs and yolk, one at a time, into the butter mixture, sifting in another 113 g of the flour-sugar mixture between each, ending with the flour-sugar. Beat each addition thoroughly.

Sift and beat in remaining 226 g of the flour-sugar mixture. Mix in the currants. Turn into prepared tin(s) and smooth batter evenly. Place on pizza stone in preheated oven and lower temperature to 325°F. Bake one hour until a tester comes out clean. Do not open the oven until for least 45 minutes. Cool 10 minutes in tin(s) on wire rack, then turn out of tin(s), remove paper and cool fully on rack.

Sources

Better Homes and Gardens. New Cook Book. New York: Bantam, 1997.

Deen, Paula. “Mama’s Pound Cake.” Food Network (2016), http://www.foodnetwork.com/recipes/paula-deen/mamas-pound-cake-recipe.html.

Farley, John. The London Art of Cookery and Housekeeper’s Complete Assistant. London, 1787.

Farmer, Fannie Merrit. The Boston Cooking-school Cook Book. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1896.

Glasse, Hannah. The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy. London, 1747.

Hess, Karen. Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995.

Jas. Townsend & Son, Ind. “1796 Pound Cakes!” Youtube (Aug 15, 2016), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sLX3d-WbaQk.

Kurlansky, Mark. The Food of a Younger Land. New York: Riverhead Books, 2009.

Lohmann, Sarah. Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

“Mary Randolph (1762-1828).” Virginia Women in History (2009), http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/vawomen/2009/honoree.asp?bio=1.

Montagné, Prosper. Larousse Gastronomique: The Encyclopedia of Food, Wine & Cookery. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1965.

Olver, Lynn. “Cupcakes,” The Food Timeline (23 January 2015), http://www.foodtimeline.org/foodcakes.html#cupcakes.

Perkins, John. Every Woman Her Own House-keeper. London 1796.

Randolph, Mary. The Virginia House-wife. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1984.

Rombauer, Irma S. Joy of Cooking. New York: Scribner, 1997.

Simmons, Amlia. American Cookery. Hartford, CT: Hudson & Goodwin, 1796.

Spiegel, Alison. “A Raisin Roundtable: Exploring America’s Love/Hate For This Controversial Snack.” The Huffington Post (03/27/2015), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/03/27/raisin-roundtable_n_6949576.html.

Virginia Federation of Home Demonstration Clubs. Recipes from Old Virginia. Richmond, VA: The Dietz Press, Incorporated, 1976.

White, Florence. Good Things in England. London: Persephone Books, 1999.

Interesting read. I’ve made a couple different recipes and use Paula Deen’s recipe.

LikeLike